17 March: Boreham on Patrick Bronte

The Head of the House

The Head of the HouseNo family in our literary history has been more talked about and written about than the Brontes; yet one member of that extraordinary household has been consistently excluded from the limelight. And he, strangely enough, is the head of the house, Patrick Bronte, the widowed father of the famous girls. Of the entire group, he is the best worth knowing and on this his birthday, we must attempt to make his acquaintance. A genial Irish gentleman with a fairly loose tongue, he loved to talk and had plenty to talk about. One would learn more Bronte lore from him in five minutes than his secretive daughters would reveal in as many years.

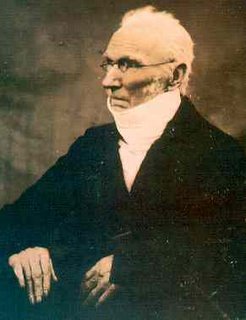

A tall, well-knit, handsome old man was Patrick. To the very end, his hair retained a suspicion of the flaming red hue that once characterised it, and his spirit held something of the sparkle of his youth. Was ever a man such a catspaw of vacillating circumstance? With troubles such as those that, in endless succession, came thundering down on the gloomy old parsonage, and with triumphs like those that, one after the other, his three consumptive girls laid at his feet, poor Patrick must have spent half his time wondering whether he was on his head or his heels.

The Boy Is Father Of The Man

The more you learn of Mr. Bronte, the more you like him. His very names are interesting. As to his surname, Mr. E. F. Benson declares that Patrick himself manufactured it. As a barefooted little urchin in County Down, his name was Brunty. But Patrick didn't like it; and why should a man be saddled for life with a name that is not to his taste? After the Battle of the Nile in 1799, Nelson, Patrick's peerless hero, was created Duke of Bronte. Brunty! Bronte! How much more musical and dignified! So Patrick made the change. As to his Christian name, there were two reasons for calling him Patrick. He was born on St. Patrick's Day, whilst a rich uncle, whom it was diplomatic to conciliate, bore that name.

The eldest of 10, Patrick was born in a poor thatched Irish cabin within sight of those Mountains of Mourne that go down to the sea. His body was nourished on an abundance of potatoes and an abundance of milk, whilst his mind was sustained on the Bible and on "Pilgrim's Progress." Once in a blue moon, as a rare treat, a microscopic allowance of meat was added to the one pabulum and a few stanzas of "Paradise Lost" to the other. But, as a reference to any astronomical calendar will show, blue moons were very scarce those days.

As a boy, Patrick's clothes were all of them home-made, a circumstance that involved him in considerable derision from boys whose suits had been bought at the city emporiums; and it is doubtful whether, until he was at least 10, Patrick's lower extremities were encased in any kind of footwear. When a vocation had to be chosen, the final selection lay between a blacksmith's shop and a weaver's shed. His own preference was for the forge rather than the loom; but when it was found that the craft of the smithy involved five years of apprenticeship, whilst one could become a weaver after serving two, the issue was decided.

Each Man In His Turn Plays Many Parts

As a weaver, Patrick was never brilliant. By this time he had become a diligent student. He read everything that fell into his hands, especially Milton. If fault was found with the warp on Patrick's web, he would plead that Milton's angels and archangels intervened between his eyes and his work. He would declaim whole pages of "Paradise Lost" to the accompaniment of the thud of the shuttle and the whirr of the wheels. In secret, too, he was doing a little poetising on his own account. He looked as unlike a budding laureate as one could possibly imagine; but a selection of these versifyings was afterwards published, together with a few stories—"The Rural Minstrel," "The Cottage in the Wood," "The Maid of Killarney," and the rest—and they certainly did him no discredit.

The pontiffs and potentates of that secluded countryside, observing the bent of his mind, secured for him an appointment as teacher at a little school at Glascar. Here Patrick covered himself with glory until, one fatal day, among the corn stacks near the schoolhouse, he was caught kissing one of his senior pupils, a bonny girl with hair as red as his own. Unfortunately, Helen, whose desk was found to be full of Patrick's love letters—some in poetry and some in prose—was the daughter of a local magnate. The thing simply wouldn't do and Patrick had to go.

But it all worked out well. In the year in which he came of age, Patrick was appointed to be teacher at Drumballyroney; approved himself to everybody; and, probably by means of monetary assistance pressed upon him by the friends he made there, passed four years at Cambridge and inaugurated that academic and clerical career of which we have an outline in the biographies of his illustrious daughters.

He retained to the last his passionate love of his Irish home and of the romantic traditions by which it was encrusted. As long as she lived, he sent his mother twenty pounds a year out of his meagre stipend. The loss of his sight was one of the crushing calamities that befell the family in the dark days in which the girls were trying to find publishers for their books. A man of great kindness of heart, a courteous host, a zealous reformer, an able preacher, and a man of wide and catholic sympathies, he was loved and honoured by his neighbours and parishioners. His attitude towards his wild and dissolute son was marked by extraordinary tenderness, understanding, and forbearance. His daughters were a constant amazement to him; but he took the greatest pride in their successes.

Losing everybody, he bore his bereavements and his blindness with exemplary courage, and, a lonely and pathetic figure, lingered on in the parsonage until, at the age of 84, he, too joined the host of Brontes that had gone down to the grave before him.

F W Boreham

Image: Patrick Bronte